de Domenico Bilotti

(Université Magna Graecia de Catanzaro)

L’histoire de la sécularisation est une histoire normative des images. Comme a été également exprimé par la Grande Chambre de la Cour de Strasbourg, en prenant des décisions relatives au recours sur l’exposition du crucifix dans les salles de classe en Italie. Tout en donnant raison, quant au dispositif, à la mémoire défensive du Gouvernement italien (l’exposition du crucifix ne viole pas l’article 9 de la Cedu en matière de liberté de pensée, conscience et religion), cette décision dégageait la relativisation des symboles religieux dans les processus avancés de sécularisation. Le crucifix n’est pas le symbole politique d’un parti, il n’exprime pas – dans un héritage culturel chrétien quand même désenchanté – une totale adhésion de foi. Ainsi, les Britanniques ou les Scandinaves reconnaissent, au mieux, dans leurs drapeaux nationaux des symboles cohérents de la communauté politique (ce n’est pas toujours vrai) mais difficilement les perçoivent comme des ascendances des cultures chrétiennes reformées ou non, d’où pourtant ils proviennent. Le symbole religieux reste évidemment un symbole de “partie”, même si transféré dans une forme sémantique distincte de celle ecclésiastique, mais la sécularisation a la force d’en désamorcer les effets séparateurs en reconnaissant le pluralisme, pour ne pas instituer aucun primat confessioniste d’une religion sur les autres. Est-ce vraiment le cas? Plus important, qu’est-ce que c’est la sécularisation?

Les spécialistes tendent à distinguer la sécularisation du sécularisme. La première est une situation de fait, qui dérive d’un processus résultatif. Tel processus consiste dans l’attribution, dans la soustraction et dans la séparation de compétences entre l’État (ou quoi qu’il en soit, les pouvoirs civils) et l’Église ( ou les formes instituées de religiosité positive). Le sécularisme consisterait, en revanche, dans une mentalité, en un habitus culturel et normatif, qui décrit une approche commune tendante au sacré.

Les deux termes ont une racine historique indiscutablement commune: les négociations pour le traité de Westphalia (1648) qui met fin à la dernière et plus âpre guerre de religion du grand siècle “longue” commencé avec la Réforme luthérienne (en 1517) et avec la confessio augustana de treize ans suivante, qui fixait la juridiction théologique interne aux nouveaux mouvements religieux. Le traité de Westphalia ne rend pas d’un coup l’Europe politique un lieu anticonfessionel du droit – comme n’arriveraient même pas à faire les révolutions bourgeois de deux siècles successifs. Il découle plutôt par une évaluation prudentielle, par un arrangement de coordination des pouvoirs (cuius regio eius religio), qui sert à faire cesser les hostilités.

Le droit publique comparé de l’Europe du XIX siècle met en lumière une étape supplémentaire institutionnel dans la déconfessionalisation de la sphère publique. Le Saint Empire romain, dans la Diète perpétuelle de Ratisbonne du 1803 (!), trois ans après sa particulièrement tardive dissolution formelle, émane la Reichsdeputationshauptschluss par laquelle vient établie la sécularisation des derniers principautés ecclésiastiques, rempart des vieux systèmes de pouvoir, et des considérables restitutions politique-patrimoniaux sont retenus aux princes laïques.

Les rapports des forces changent: the times they are a-changin’.

Depuis, le débat sur la sécularisation et ses effets est très large. A-t-il signifié l’émancipation d’exigences juridiques et normes coutumières restrictives et basées sur un moralisme intrusif et préconditionné? Ou a-t-il désacralisé complètement le discours commun, en le conservant stérile par les limites étiques auxquelles on demandait, en dernier, la fondamentale fonction de “servare societatem”?

Quelle que soit notre réponse — la plus exacte devrait, toutefois, se situer de manières à ne pas légaliser tout comportement et à ne pas abolir toute instance immatérielle dans les rapports sociaux —, l’idée que la sécularisation soit un processus exclusivement euro-occidental s’est frayé un chemin.

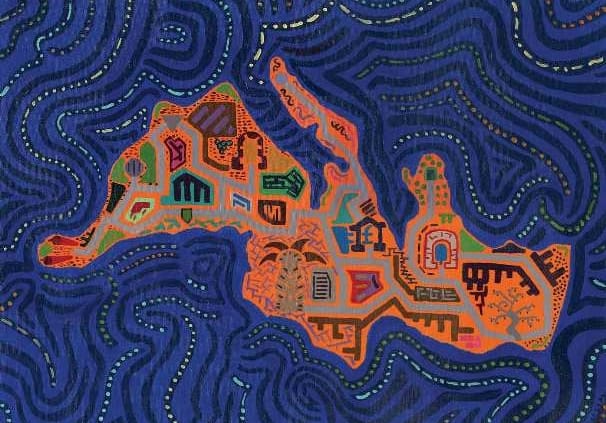

Encore une fois: l’affirmation peut être correcte si nous échangeons le processus de sécularisation avec son particulier divenir historique en Europe et en Occident. Pas comme ça si on considère que toute civilisation est marquée par instances de libération par les formes théologiques du contrôle politique. La sécularisation dans la Méditerranée arabe-islamique n’est pas absente, il s’agit d’une lutte civile juste plus récente: c’est le fjord d’un parcours qui s’est engagé beaucoup plus tard, aussi parce que l’unification des peuples sous l’égide d’un monothéisme abrahamique d’orientation fortement aggregative est postérieure à la dynamique européenne des rapports entre autorités civiles et religieuses.

L’islamisation arrive après la christianisation et, au-delà des points en commun, le droit islamique et le droit civil qui jaillit de la tradition romain-canonique, non seulement au même point de leur parabole.

Les institutions publiques du monde arabe-méditerranéen confirment empiriquement cette suggestion théorique et reconstructive à travers des exemples de conduite qui ne concluent pas le raisonnement, mais qui en indiquent les point centraux.

Le secularisme arabe ne se propose pas en tant qu’ouvertement anti-islamique: au contraire, il opère souvent comme un vrai mode d’action, procédural et substantiel, en préservant le noyau de valeur de foi contre ingérence gouvernementales, hiérarchiques, militaires. Au fond, même les premiers penseurs occidentaux, dont la réflexion servit de toile de fond à une pacification sociale ordonnée sur la séparation des pouvoirs, se proposaient en tant qu’hommes de foi et spiritualité authentiques, comme peut-être qu’ils étaient. Le secularisme arabe a une caractéristique ultérieure: ne se propose pas seulement comme le linteau, certes important, de droits civils individuels (comme il avait été pendant l’état liberal du XIXe siècle, qui les relisait toutefois sous le chapeau des statuts propriétaires), mais il se dit encore plus comme volant communautaire intégral de justice sociale.

Ainsi, il a l’opportunité historique de se présenter également comme formidable instrument d’émancipation anti-colonial, bien que une telle instance risque de fermenter un concept de “nation”, contre despotes et colonisateurs, d’abord pour bonne part étranger à la culture arabe.

En sont l’éprouve les histoires de l’algérien Ahmed Ben Bella (1916-2012), du marocain Mehdi Ben Barka (1920-1965) et, sans surprise, du palestinien de formation chrétienne Nayef Hawatmeh (1935). Ils donnent vie aussi sur le plan jusecclésiastique et philosophique-juridique, à trois différentes et non opposées façons de repenser l’islamique politique et le secularisme arabe d’orientation socialiste.

Bella est le premier président de l’Algérie libre, il ne pense pas à la République en termes laïques, même parce que le régime juridique, très mal perçu et finalement battu envahisseur français, est laïque-séculier.

Il immagine l’ordre révolutionnaire en termes de radicale émancipation politique, mais cette lutte de partie (et aussi “de classe” selon Bella) appartient désormais au vécu historique du peuple algérien, si même la réforme constitutionnelle di 1986 conserve dans le Préambule tribut non purement honorifique aux “pères” du Front de Libération national.

Barka a connu un sort moins enviable. Tué à Paris à la suite d’une opération des services secrets, qui n’est pas sans rappeler celle subie par l’iranien Shariati, un peu plus d’une décennie plus tard à Londres.

La raison anticolonialiste, dans le contexte d’une lutte politique qui se présente sur le front ouvert de la sécularisation, s’associe ici à un plus systématique effort tiers-mondiste: Barka est une référence du fond de solidarité afro-asiatique qui soutien économiquement et politiquement les pays non alignés. Entre l’appétit post-colonialiste des puissances occidentale et les ambiguïtés soviétique dans le rapport avec les pays arabes, l’Islam peut maintenir une valeur ordonnatrice universelle, même sur le plan politique, s’il accepte des modules constitutionnels fédéralistes, pluralistes et anti-autoritaires.

Il n’y a toujours aucune séparation de juridictions entre le précepte (religieux) et la norme (qui dicte l’obligation politique), mais on accepte l’idée que leurs rapports ne puissent pas faire abstraction de compétences simplement contingentes différentes.

C’est Hawatmeh qui, du chaudron palestinien, approfondit dans les décennies le spectre théorique de ces options. Hawatmeh ambitionnerait de substituer l’État d’Israel avec une confédération palestinienne, d’orientation bien évidemment anti-sioniste et panarabe (imposer le panarabisme aux peuples et aux États arabes il lui semble une façon d’éterniser, sous les vestiges d’une foi indivisée, les mêmes pouvoirs qui ont lutté et luttent dans les conflits militaires).

Ces trois Auteurs ne prônent pas l’inclusion institutionnelle du principe de laïcité: affirmer le contraire serait un forçage non satisfaisant sur le plan technique-juridique. Ils accueillent et soutiennent, toutefois, à différents degrés, les axes fondateurs du “jeu” démocratique: tripartition institutionnelle-organisationnelle des pouvoirs, reconnaissance des autonomies territoriales, intervention de l’État à des fins de redistribution économique, cessation de prétentions juridictionnelles et administratives par des élites religieuses. C’est un programme politique à des années-lumière du fondamentalisme et également loin du socialisme arabe nationale, expérimenté sous les dictatures en Syrie et en Iraq, où on visait à substituer les précédents régimes avec un mythe fondateur national qui englobât à sa façon et à son profit les codes obligatoires de dérivation religieuse. Bella et Hawatmeh montrent donc une spéculation (ϑεώρησις) legale qui accueille certaines des mêmes nécessités sociales qui motivèrent plus des trois siècles auparavant, le début de la sécularisation occidentale. En particulier: l’anti-autoritarisme, auto-determination et la pacification interétatique afin de garantir essentiellement les meilleures conditions de vie pour tous. La sécularisation, même lorsqu’elle est saisie dans ses présupposés embryonnaires et non mûrs, peut être un mosaïque de différences, dans des cadre de liberté. D’autant plus dans notre changeant échiquier méditerranéen.

Traduzione in francese a cura di Laura Paulizzi